Reports of healthcare worker shortages amid stubborn COVID-19 surges — and the lingering aftershocks of the first waves of the novel coronavirus — have been growing in urgency in 2022, and now in at least one case it’s been quantified: 17,061

That’s the number of job openings near the end of the first quarter of 2022 at six of the top hospital systems in the U.S., as calculated by Becker’s Hospital Review. The publication took U.S. News & World Report’s best hospital rankings and focused on six systems across the country to illustrate staffing challenges as the global pandemic enters its third year.

And it’s not just COVID-19 that’s causing this shortage, though that has accelerated the number of healthcare professionals leaving their jobs and the industry. There are also housing costs and natural attrition. Taken in total, it paints a picture of an industry facing what one prominent group calls “a national emergency,” one attracting national attention and coverage from venerable news programs such as 60 Minutes.

Healthcare staff shortages, while not new, have spawned a world today where it can take five hours to get an X-ray for a dislocated elbow and another two to get pain medication for the injury. Ambulances sometimes wait eight hours to drop off a patient, and nurses work 12- to 16-hour shifts, without a food break.

About 400,000 healthcare workers have left jobs since the start of the pandemic, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Worldwide, healthcare workers also struggle with COVID cases — often with far fewer resources.

Alleviating staffing challenges with single-use

Throughout the pandemic, hospitals have had to implement innovative approaches to soften staffing shortages, from aggressive recruiting programs to bonuses. Labor shortfalls impact medical device companies, as well, by dragging down procedure volumes at a time when the U.S. and other countries are getting better at managing COVID-19 surges.

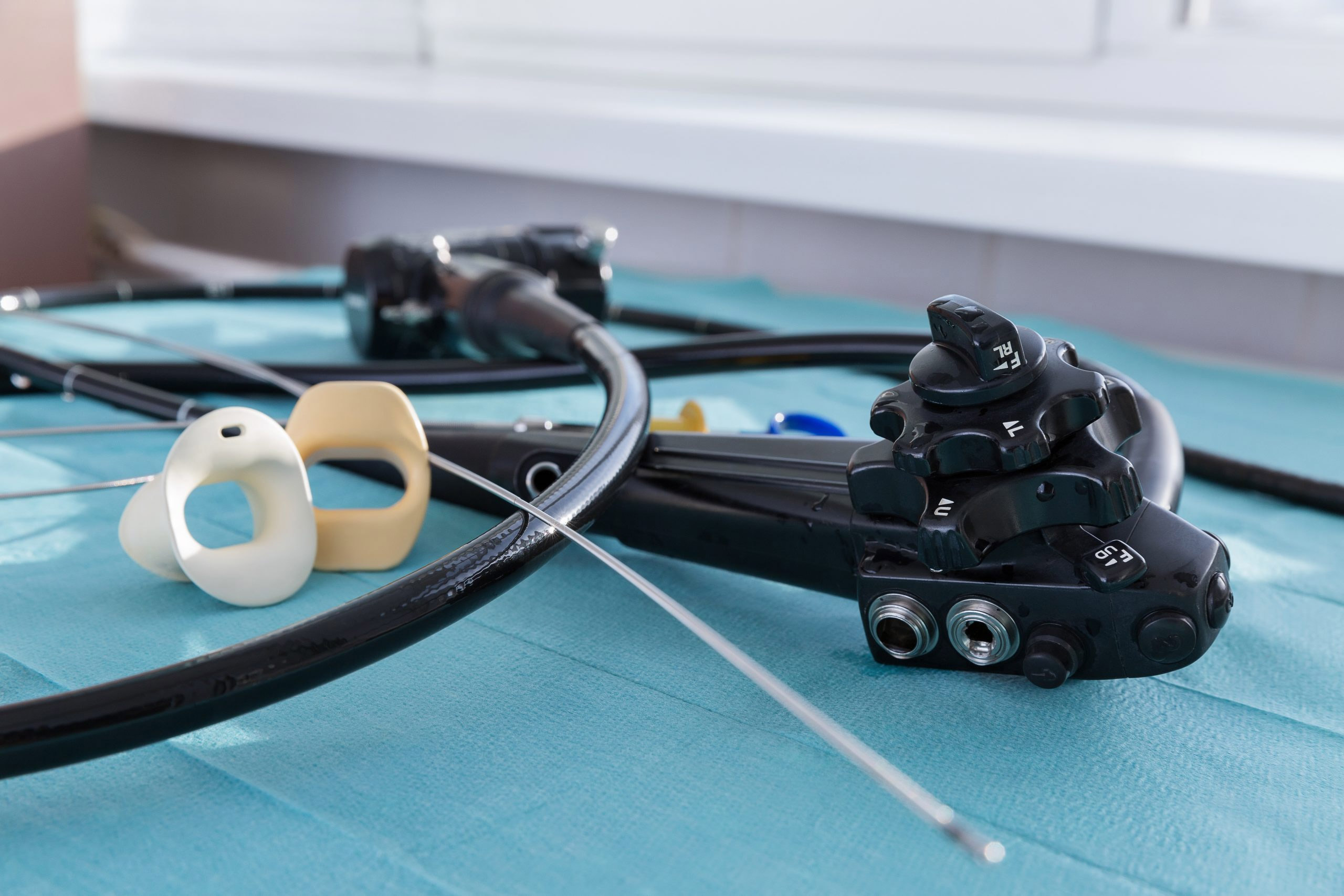

In response, medical device companies are also getting innovative. Endoscopy companies, for example, are touting single-use scopes as a tool to address staffing shortages: Flexible bronchoscopes and cystoscopes, made by companies such as Boston Scientific Corp. and Ambu A/S, are always available and are sterile straight from the pack.

This means that, unlike traditional endoscopes, they don’t require extensive staffing — for preparation, transport, reprocessing, and often direct procedure support. They can be simply used once and discarded.

That dovetails with efforts by hospital administrators to alleviate workflow burdens on healthcare professionals. Officials with the American Medical Association, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, and other organizations have crafted what they call a workforce rescue package to ease the burden on hospital staffers.

One action item: “Getting Rid of Stupid Stuff,” which zeros in on workflow inefficiencies and includes reducing electronic health record clicks and notifications and eliminating unnecessary mandatory training requirements.

Single-use endoscopes don’t require extensive training for staffers on complex reprocessing protocols because reprocessing isn’t necessary.

Could shortages get worse?

The supply of healthcare workers was a problem long before the pandemic and might get worse. Schools are not minting enough healthcare professionals to meet demand, even as baby boomers age and need more care. In fact, demand for healthcare workers will outpace supply by 2025, according to a Mercer analysis.

The American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) predicts a shortage of up to 122,000 physicians by 2032, as the over-65 population will grow by 48 percent. With the average age of a physician at 53.2 years old in 2021, many physicians soon will reach retirement age.

By 2026, physicians of retirement age will rise from 12 percent to 21 percent, according to the report.

At the same time, the Association of Colleges of Nursing suggests that the U.S. will need more than 200,000 new nurses every year until 2026.

The healthcare worker shortage is not isolated to the U.S. The World Health Organization (WHO) projects a shortfall of 18 million healthcare workers worldwide by 2030.

Pandemic accelerating attrition

The pandemic has led some healthcare workers to retire early, according to the Mercer report.

“The healthcare workforce is burned-out following a nearly two-year face-off against COVID-19,” said John Derse, healthcare industry vertical leader at Mercer, in a Fierce Healthcare post. “This impact will be felt by all of us, regardless of where we live or our field of work.”

Another huge impact is that so many healthcare workers have gotten sick themselves.

Acute impact on patients

More than half of all Americans say they have felt healthcare worker shortages, according to a recent CVS Health-Harris Poll National Healthcare provided to Axios.

The shortages show up in delayed surgeries, cancelled appointments, and difficulty even scheduling visits because many doctors have reduced hours. Thirteen percent of survey participants say their health care facility closed completely, according to the survey.

In various places around the world, long wait times for routine endoscopies are the new normal.

“Patients are losing patience,” says John Gerzema, CEO of the Harris poll.

‘A perfect storm’ in hospitals

A Minnesota nurse speaking to a state legislative committee described being “simply overwhelmed” and nurses working 12- and 16-hour shifts.

“It’s sort of the perfect storm,” Minnesota Health Commissioner Jan Malcolm testified during a recent legislative hearing. “An already taxed system, a tsunami of cases, a lower proportion of which would still net more numbers needing hospitalization at a time when staffing is lower than it has been and the system is incredibly, incredibly stressed from this long and arduous marathon.”

In L.A. County, Calif., ambulances can be tied up longer than eight hours, unable to answer other calls, while patients await a bed, Jeff Lucia, communications director for one ambulance provider, told the Los Angeles Times.

“This pandemic will end,” says Dr. Jason Smith, chief medical officer at the University of Louisville Hospital. “All pandemics end. But it's the carry-forward from what we're having to do, and the amount of human capital that we're burning through right now, that are going to impact the health care system for the next two, five, 10 years.”