For Dr. Marybeth Spanarkel, GI endoscopy was a labor of love.

“There is an immediate gratification in performing a procedure and getting an almost immediate answer,” Spanarkel said of colonoscopy and upper GI endoscopy.

Unfortunately, after 28 years in private practice at the Duke University Regional Hospital in Durham, North Carolina, Spanarkel suffered a career-ending neck injury that caused sudden paralysis in her right arm. Despite multiple surgeries and months of physical therapy, she has never been able to regain full strength in her arm — losing the ability to perform the endoscopy procedures she enjoyed so much.

Unfortunately, after 28 years in private practice at the Duke University Regional Hospital in Durham, North Carolina, Spanarkel suffered a career-ending neck injury that caused sudden paralysis in her right arm. Despite multiple surgeries and months of physical therapy, she has never been able to regain full strength in her arm — losing the ability to perform the endoscopy procedures she enjoyed so much.

“I’m one of those physicians who ended up totally disabled from a musculoskeletal injury,” Spanarkel said in a recent interview with Single-Use Endoscopy. “It brought my career to an abrupt end at 59 years of age. And I’m sort of a workaholic, so I would have easily practiced another 10 or 12 years.”

Rather than walk away from the field altogether, Spanarkel has channeled her energy into keeping other GI endoscopists from suffering the same fate. She is now a medical advisor for ColoWrap®, an abdominal compression device used to mitigate ergonomic challenges as they relate to the phenomenon of looping in colonoscopy.

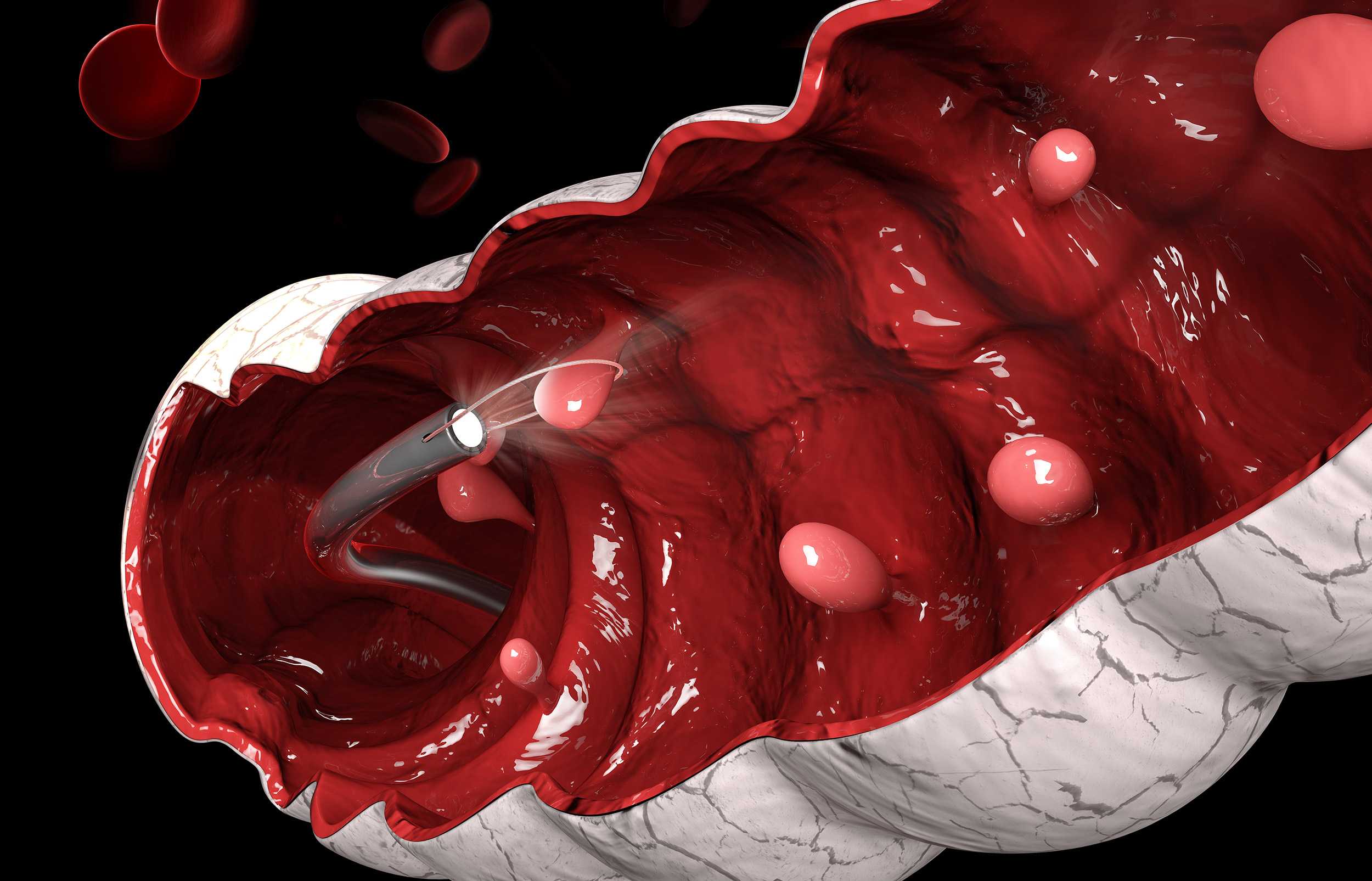

Looping refers to twists and turns that occur in the colonic anatomy as the scope is inserted forward through the GI tract. The various techniques employed to mitigate or reduce looping may require great physical exertion on the part of the endoscopist to maneuver and advance the scope. Prior to the development of this compression device, the only tools available to the endoscopist involved manual compression on the abdomen by an assistant or repositioning the patient.

Spanarkel recently shared more about her experiences as a female clinical endoscopist and the unique ergonomics challenges that colonic looping presents.

“I am absolutely passionate about reducing the propensity of musculoskeletal injuries and prospective disabilities in my colleagues,” she said. “If women go down with these injuries, it certainly hinders their forward career, both academic and clinical.”

SUE: A recent survey from the American College of Gastroenterology found most participating gastroenterologists (71 percent) reported an endoscopy-related injury in their career. When did you first start to notice pain related to work?

Spanarkel: Early in my practice, I was one of the few female gastroenterologists in my locale and there were lots of female patients who were requesting me. So, I was very, very busy. Over the course of 20 to 30 years of practice, I often had aches and pains related to overuse. I had pain in my right hand and my right shoulder. I had pain in my left thumb, all of these now well-described musculoskeletal injuries related to overuse. And then suddenly, I had a very minor injury at home which caused this sudden extrusion of a disc which clipped the nerve to my right arm and my career was over.

Despite the devastating realization that I could no longer practice as a GI physician, I began to investigate the perils of overuse syndromes in GI physicians, what were the actual problems, and how could we begin to solve them.

SUE: Were you able to pinpoint any one cause for musculoskeletal injury in your practice?

Spanarkel: When I look back on my career, what were the problems? Well, the more endoscopies you do, the higher your risk of injury. Anything you do more repetitively, the higher damage you can do to your muscles and joints, particularly if you’re not trained. You’re standing all day long. You’re standing potentially in an awkward position. And these issues can be addressed rather quickly and simply. Put a pad under your feet, stretch between procedures, get your stretcher at the right height, get your eye monitors at the right height.

But, the one issue that I retrospectively thought contributed the most to my musculoskeletal damage (and the issue most ignored) was the problem of looping during colonoscope insertion, the pushing, pulling, torquing required to get the colonoscope to the cecum.

And, more importantly, it was hurting staff and endoscopy nurses because they are required to apply extensive manual compression on the abdomen to help the scope get around. It was really kind of barbaric — I always use that word when I talk about it — pushing on somebody’s belly with tremendous forces, and using hands, elbows, and forearms, just to get the scope around. It is kind of crazy.

SUE: Why does looping present such ergonomic challenges?

Spanarkel: Looping is one of the most difficult parts of learning how to do a colonoscopy. Most of the time it is the single thing that makes colonoscopies difficult.

If you bump into looping, the procedure takes longer, you have to scope and then pull it back and torque to the right. You’re turning your wrist to the right as you’re pulling the scope. And your left thumb is wiggling the dials so that the tip of the scope will angulate in different positions. All of that requires a lot of push and pull and torqueing and turning and you have to exert forces on that scope that can be tough.

So, I realized that this single problem, trying to mitigate looping, was the one thing that probably cost me [use of] my arm. And thus, I began to develop a compression device to solve this problem for both physicians and staff alike — the birth of the ColoWrap.

SUE: Are there unique challenges women might face when it comes to looping compared with their male colleagues?

Spanarkel: I think I had a little bit more requests from female patients to have a female doctor. Sometimes that’s just patient preference.

I will tell you that having done way more females than males in my practice, particularly when I first started, that these are often tougher colonoscopies. The reason is that women have pelvic organs such as the uterus and ovaries. Some women have had c-sections or hysterectomies. The long and short of that is, the more you have to navigate and the more potential for pelvic scar tissue, the more likely looping is to occur. Therefore, often, female patients can be a very difficult colonoscopy.

Also, if you’re a female vs. a male endoscopist, your hand is smaller, your stature and your musculoskeletal development may be not quite as strong as the male. These scopes are heavy. Doing this all day long, by the end of the day, you’re exhausted.

SUE: In an ACG survey, two-thirds of participating gastroenterologists (67 percent) reported receiving no ergonomics training in residency. Do you think enough attention has been paid to ergonomics in the endoscopy suite?

Spanarkel: The problem with ergonomics, interestingly, in the United States, is that there has been almost a peculiar denial — or perhaps a lack of interest — in the fact that one in five physicians is getting injured and one out of three or four staff members is getting injured. People are not really cognizant of what that means.

Number one, look at what happened to me. My career ended 10 years early. I was in a five-member colonoscopy group. Immediately, 20 percent of the revenue of the outpatient unit went down because I was a fairly productive member.

If a nurse goes down in one of these units from back pain, or carpel tunnel, or a neck injury, we have data to show that it costs the endo unit a minimum of $100,000 to $120,000 for every nurse that gets injured in workman’s comp, in days lost, in days missed.

SUE: When you think about the next generation of GI endoscopists, why would you advocate for more ergonomics training?

Spanarkel: Women typically start to complain after five years of performing endoscopic procedures, and men start to complain around seven years of injury. That’s a short time in a 30-year career.

My daughter is currently finishing her training in advanced endoscopy and she is already addressing problems with her neck and her back. They say that in GI training, within the first six months of training, 70 percent of all the fellows complain of some musculoskeletal pain.

And there is a lot of interest in ergonomics right now because people are becoming aware that we have got to increase the volume of these procedures. The age for colorectal cancer screening has now gone down to 45; that means we are going to have to do more screening procedures. And the more you do, the higher the risk you are for musculoskeletal injuries.